Far beneath the ocean’s surface lies one of Earth’s most powerful yet least understood climate allies: the deep sea. Covering more than half of the planet, deep-sea benthic ecosystems—communities of organisms living on or in the ocean floor—play a crucial role in long-term carbon storage. For decades, however, human activities such as bottom trawling, seabed mining exploration, and infrastructure development have disrupted these fragile environments.

Recent scientific observations reveal an encouraging trend. After deep-sea disturbances were limited or halted, benthic ecosystems began to recover—and with that recovery came a renewed ability to store carbon. These findings highlight the deep ocean’s overlooked role in climate regulation and underscore the importance of protecting seafloor habitats as part of global climate strategies.

The Deep Sea’s Role in the Global Carbon Cycle

Carbon storage in the ocean is not confined to surface waters or coastal wetlands. The deep sea acts as a vast, long-term carbon reservoir, locking away organic carbon for centuries or even millennia.

This process is driven by what scientists call the biological carbon pump. Phytoplankton at the surface absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. When these organisms die or are consumed, carbon-rich particles sink through the water column and settle on the seafloor. There, benthic organisms help bury and stabilize this carbon within sediments.

Once stored in deep-sea sediments, carbon is effectively removed from the atmosphere for geological timescales—making these ecosystems critical allies in slowing climate change.

What Are Benthic Ecosystems?

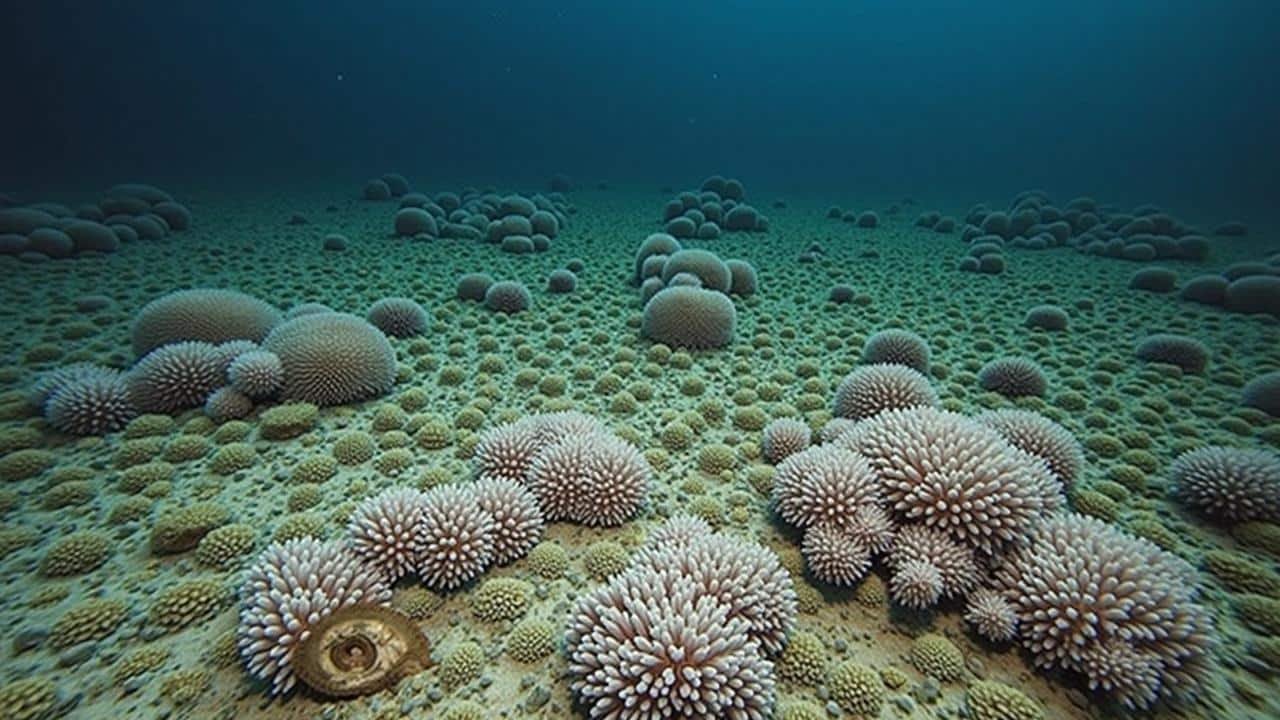

Benthic ecosystems consist of organisms that live on, in, or near the ocean floor. These include:

- Invertebrates such as worms, sea cucumbers, and crustaceans

- Benthic fish species

- Microbial communities within seabed sediments

- Cold-water corals and sponge fields

Together, these organisms regulate sediment structure, oxygen levels, and nutrient cycling. Their activity determines whether carbon remains safely buried or is disturbed and released back into the ocean.

Human Disturbance on the Ocean Floor

Although the deep sea was once thought to be largely untouched, advances in technology have expanded human activities into previously inaccessible depths.

Bottom Trawling

Bottom trawling is among the most destructive practices affecting benthic ecosystems. Heavy fishing gear dragged along the seabed can:

- Resuspend sediment and stored carbon

- Destroy complex habitats like coral and sponge gardens

- Reduce biodiversity and organism density

In heavily trawled areas, decades of accumulated carbon can be released in a single pass.

Seabed Mining Exploration

Interest in deep-sea mining for minerals such as cobalt, nickel, and manganese has grown rapidly. Even exploratory activities disturb sediments, creating plumes that can spread for kilometers and smother benthic life.

These disturbances disrupt the natural burial of carbon and can shift sediments from long-term storage sites into active carbon cycling, increasing the risk of carbon re-release.

Infrastructure and Cable Laying

Subsea cables, pipelines, and drilling operations also contribute to seabed disturbance. While localized, repeated or widespread installations can fragment habitats and alter sediment dynamics.

What Happens When Disturbance Is Reduced?

In areas where deep-sea disturbances were restricted—through fishing closures, protected zones, or regulatory limits—scientists observed gradual but meaningful recovery.

Sediment Stability Improved

Without repeated physical disruption, sediments began to settle and compact naturally. Stable sediments are better at trapping organic carbon and preventing its resuspension into the water column.

Benthic Fauna Recovered

As physical damage ceased, slow-growing benthic organisms began to return. Burrowing species played a key role by:

- Mixing organic matter deeper into sediments

- Enhancing microbial processes that stabilize carbon

- Increasing oxygen penetration without releasing stored carbon

This biological activity restored the balance needed for long-term sequestration.

Microbial Carbon Processing Resumed

Microbes are the unseen engineers of carbon storage. In undisturbed sediments, microbial communities efficiently convert organic matter into stable forms of carbon that remain buried.

After disturbance was limited, microbial diversity increased, and carbon mineralization slowed—meaning more carbon stayed locked in sediments rather than returning to the water column as CO₂.

Evidence from Protected and Restricted Zones

Marine protected areas (MPAs) and fishing exclusion zones have provided valuable real-world laboratories. In several deep-sea regions, researchers found that sediments inside protected areas held significantly more organic carbon than nearby disturbed zones.

Even partial restrictions—such as seasonal trawling bans or depth limits—were associated with improved carbon retention over time. While full recovery can take decades, the direction of change was consistently positive once disturbance stopped.

Why Recovery Takes Time

Deep-sea ecosystems operate on much longer timescales than shallow or terrestrial environments. Many benthic species grow slowly, reproduce infrequently, and rely on a steady but limited supply of organic matter from surface waters.

As a result:

- Habitat recovery may take decades

- Carbon storage capacity increases gradually

- Some damage may be irreversible in heavily disturbed areas

This slow pace makes prevention of disturbance far more effective than attempting restoration after degradation.

Climate Implications of Benthic Carbon Storage

The resumption of carbon storage in deep-sea sediments has major implications for climate mitigation. Carbon released from disturbed sediments can re-enter ocean circulation and eventually reach the atmosphere.

By protecting benthic ecosystems, we:

- Prevent the release of stored carbon

- Maintain long-term sequestration pathways

- Strengthen natural climate regulation systems

Unlike technological carbon capture, benthic carbon storage requires no energy input—only protection from disruption.

Policy and Conservation Opportunities

Recognizing the climate value of deep-sea ecosystems opens new avenues for policy action.

Potential strategies include:

- Expanding deep-sea marine protected areas

- Restricting bottom trawling in sensitive habitats

- Regulating seabed mining before large-scale extraction begins

- Incorporating benthic carbon into climate accounting frameworks

Protecting the deep ocean could become a cost-effective component of global climate policy.

A Hidden Ally Beneath the Waves

The recovery of carbon storage following reduced deep-sea disturbance sends a clear message: the ocean floor is not an inert wasteland, but a living system with profound influence over Earth’s climate.

Benthic ecosystems quietly perform one of the planet’s most important services—locking away carbon far from the atmosphere. When human activity disrupts these systems, that service is compromised. When we step back, nature begins to repair itself.

Conclusion: Protection as Climate Action

After limiting deep-sea disturbance, benthic ecosystems resumed carbon storage—not through engineered solutions, but through the restoration of natural processes that have operated for millions of years.

As climate challenges intensify, protecting the deep sea offers a powerful, underappreciated opportunity. By safeguarding benthic habitats today, we preserve one of Earth’s most reliable carbon sinks for generations to come.