For decades, modern agriculture has been locked in a difficult balancing act: producing enough food for a growing global population while protecting the natural systems that make farming possible in the first place. Intensive plowing, monocropping, heavy chemical use, and land clearing boosted short-term yields—but often at a steep environmental cost. Among the most serious consequences were widespread soil erosion and a dramatic loss of biodiversity.

In recent years, however, a growing number of farmers, researchers, and policymakers have begun to rethink how food is grown. The results are encouraging. Across many regions, changes in agricultural practices have led to measurable declines in soil erosion and significant increases in biodiversity—proving that productive farming and ecological health do not have to be opposing goals.

The Hidden Crisis of Soil Erosion

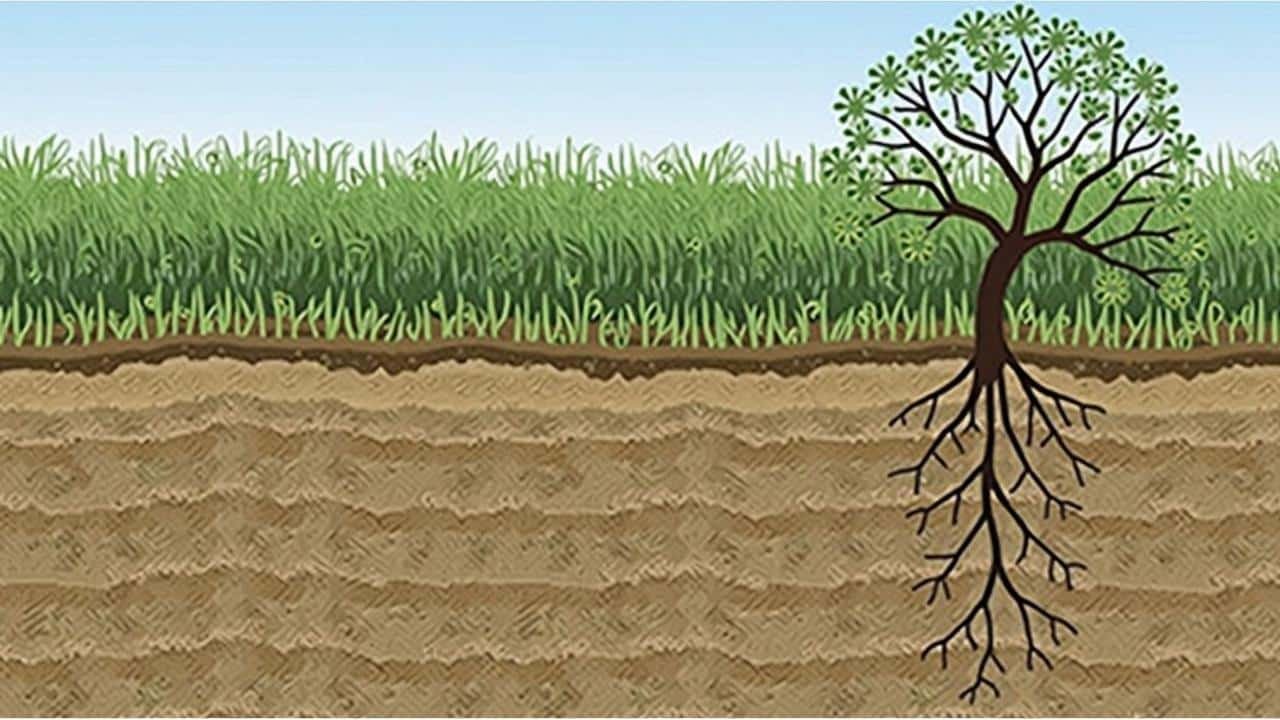

Soil erosion is often invisible until the damage is severe. Wind and water gradually carry away the nutrient-rich topsoil that crops depend on, leaving behind compacted, less fertile ground. According to agricultural scientists, it can take hundreds of years to form just a few centimeters of healthy topsoil—yet it can be lost in a single season of poor land management.

Traditional practices such as deep tillage and leaving fields bare between planting seasons make soil especially vulnerable. When rainfall hits exposed soil, it washes particles into nearby streams and rivers, contributing to sedimentation, water pollution, and flooding downstream.

Erosion doesn’t just reduce yields. It weakens soil structure, lowers water retention, increases dependence on fertilizers, and ultimately threatens long-term food security.

Biodiversity Loss: The Other Side of the Coin

At the same time that soil was being depleted, farmland biodiversity declined sharply. Hedgerows were removed, wetlands drained, and diverse crop rotations replaced by vast monocultures. Beneficial insects, birds, microbes, and native plants disappeared from agricultural landscapes.

This loss had cascading effects. Fewer pollinators meant lower crop resilience. The absence of natural predators led to pest outbreaks. Soil microbial communities—essential for nutrient cycling—became less diverse and less effective.

In many cases, farmers responded by increasing chemical inputs, which further harmed ecosystems and locked agriculture into a cycle of dependency.

A Shift Toward Regenerative Thinking

Recognizing these problems, many farmers have begun adopting alternative practices rooted in soil health and ecosystem function. Often grouped under terms like regenerative agriculture, conservation agriculture, or agroecology, these approaches focus on working with natural processes rather than against them.

Key principles include:

- Minimizing soil disturbance

- Keeping soil covered year-round

- Increasing plant diversity

- Integrating livestock responsibly

- Reducing synthetic chemical inputs

While these ideas are not new, their widespread adoption marks a significant shift away from extractive farming systems.

Reduced Tillage: Letting Soil Stay Put

One of the most impactful changes has been the reduction—or elimination—of tillage. No-till and low-till systems leave crop residues on the soil surface, protecting it from wind and rain.

The benefits are clear:

- Soil particles are less likely to be washed away

- Organic matter accumulates over time

- Soil structure improves, increasing water infiltration

- Earthworms and microorganisms thrive

Studies have shown that no-till fields can experience dramatically lower erosion rates compared to conventionally plowed land, particularly on slopes or in regions with heavy rainfall.

Cover Crops: Nature’s Protective Blanket

Another practice driving positive change is the use of cover crops—plants grown between cash crops not for harvest, but for soil health.

Cover crops such as clover, rye, vetch, and radishes:

- Anchor soil with living roots

- Prevent erosion during fallow periods

- Add organic matter when decomposed

- Support beneficial insects and microbes

Fields that once sat bare for months are now alive year-round, reducing nutrient runoff and creating habitat for a wide range of organisms.

Crop Diversity Brings Life Back to the Land

Monocultures simplify farming operations, but they also simplify ecosystems—and simplified ecosystems are fragile. By reintroducing crop rotations, intercropping, and agroforestry, farmers are restoring complexity to their fields.

Diverse plant systems:

- Break pest and disease cycles

- Support a wider range of pollinators

- Improve nutrient availability

- Increase resilience to climate extremes

Biodiversity above ground is closely linked to biodiversity below ground. When plant diversity increases, soil microbial communities become more complex and efficient, further improving soil stability and fertility.

Restoring Field Margins and Natural Features

In many regions, farmers are also restoring features once considered unproductive: hedgerows, buffer strips, wetlands, and grassed waterways.

These areas play a critical role in reducing erosion and boosting biodiversity by:

- Slowing water flow during heavy rains

- Trapping sediment before it reaches waterways

- Providing habitat for birds, insects, and small mammals

- Connecting fragmented ecosystems

What was once seen as “wasted space” is now recognized as essential infrastructure for healthy agricultural landscapes.

The Return of Beneficial Wildlife

As farming practices change, wildlife responds quickly. Pollinator populations increase when flowering cover crops and field margins return. Birds nest in hedgerows. Predatory insects help control pests naturally.

This resurgence of biodiversity reduces the need for chemical interventions, saving farmers money while improving environmental outcomes. In some cases, farmers report more stable yields because their crops are better protected by functioning ecosystems.

Economic and Social Benefits for Farmers

Improved soil health and biodiversity are not just environmental wins—they also make economic sense. Healthier soils retain water more effectively, reducing irrigation needs during droughts. Improved nutrient cycling lowers fertilizer costs. Reduced erosion means fields remain productive for generations.

Additionally, farms using sustainable practices often gain access to:

- Premium markets

- Certification programs

- Government incentives

- Increased consumer trust

As public awareness of environmental issues grows, farmers who protect land and biodiversity are increasingly recognized as stewards of shared natural resources.

A Model for the Future of Food

The decline in soil erosion and the recovery of biodiversity demonstrate that agriculture can be both productive and restorative. These successes challenge the assumption that environmental protection must come at the expense of food production.

While no single practice is a universal solution, the evidence is clear: when farmers change how they work the land, the land responds positively.

Conclusion: Healing the Soil, Reviving Life

By changing agricultural practices, soil erosion has declined and biodiversity has increased—not by accident, but by intention. These outcomes reflect a growing understanding that healthy soils and thriving ecosystems are the foundation of resilient food systems.